July 6th’s piano recital is unabashedly bathed in Chopin. Which is something I never thought I’d do. Not because I don’t love Chopin, but because his pieces were such a mainstay in my student and competition days that I just needed a breather from all those Ballades and Scherzos. And as the years went on, it began to feel rather indulgent to perform Chopin when the greatest pianists had already recorded his works so masterfully.

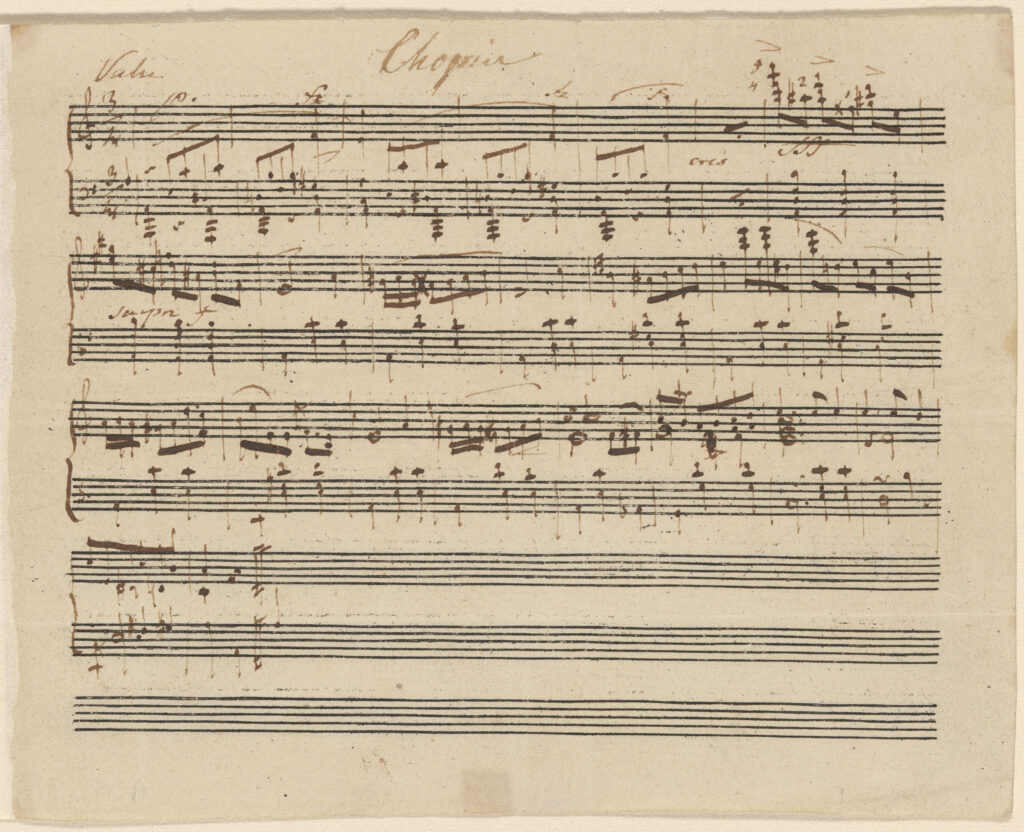

Quite honestly, the idea came about because my former teacher, Logan Skelton, had emailed me his latest project, his completion of Chopin’s recently discovered waltz in the Pierpont-Morgan Library. This is a very Skelton thing to do. Logan loves to continue the unfinished works of past composers, much to the delight of his students, and especially to the delight of this former student.

The sketch had been mixed in a pile of unsorted memorabilia, and because it was written on a scrap of paper the size of an index card, one can see how it could have been missed.

It’s a novel experience to premiere a never before heard piece by the composer who died 176 years ago, which is made even more unique because we’re so familiar with Chopin’s music. There’s also a whiff of the clandestine, because Chopin was very clear that he never wanted any of his unpublished music to see the light of day.

“There were infinitely more secular matters than sacred ones pressing on Chopin’s mind. He had frequently expressed the wish that all his unpublished manuscripts be burned after his death. A few hours before he expired he charged his compatriot Grzmala with this difficult task, who reported his heavy responsibility to their friend Auguste Léo.

‘There will be found many compositions more or less sketched,” he told me. “In the name of the friendship you bear me I ask that they should all be burnt, with the exception of the beginning of a [piano] method which I bequeath to Alkan and Reber to see whether any use can be made of it. The rest without exception must be consigned to the flames, for I have always had a great respect for the public and whatever I have published has always been as perfect as I could make it. I do not wish that under the cover of my name works that are unworthy of the public should be spread abroad.’ (Walker, 2018, p.617)

Walker, Alan. “Fryderyk Chopin: A Life and Times.” Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018.

While this is an understandable desire of a composer to self edit their own legacy, sometimes we all need someone else to point out our value. And so, we’re all delighted that Chopin’s people did not follow his instructions.

Because the sketch is sort of a doodle, (fun fact – Chopin enjoyed doodling little self portraits on some of his manuscripts), Logan was inspired to imagine how Chopin might have completed the piece himself. In his own words:

“It is exactly the sort of cast off, sketchy thing that Chopin deeply wanted never to see the light of day. Knowing how he felt, that’s why I thought of trying to bring the fragment into some sort of performable state, an attempt to use the thematic material as Chopin might have done. It is 100 percent impossible to say what he might have made of it, of course. I would have been fascinated to see, as would we all. But I guess it strikes me as less of a betrayal of Chopin’s final wishes to take this homeless and abandoned thematic material and make some sort of presentable piece out of it, rather than just leaving it in its fragmentary and quite unfinished state”.

And because I feel like Chopin’s 24 Preludes are the best thing he wrote, those naturally became the centerpiece of the program. The set, which is meant to be performed in their entirety, are such concentrated bullets of extreme emotion. Many of them were composed when Chopin was traveling in Majorca and suffering from his first major attack of tuberculosis, shut up in a creepy abandoned monastery because the locals refused to house him for fear of contamination. Combine the gothic setting, stormy weather, and the fact that the local doctor pronounced him at death’s door, and the vivid despair just bleeds off the page.

Caroline Shaw’s Gustave le Gray provides a balm with her musical frame of Chopin’s Op.17 no.4 mazurka, which lies at the center of the work. Her love for the piece is evident in her foreward:

“Chopin’s opus 17 A minor Mazurka is exquisite. The opening alone contains a potent poetic balance between the viscosity and density of the descending harmonic progression and the floating onion skin of the loose, chromatic melody above”.

The frame is both Caroline’s blending of Chopin’s language with her own, as well as a translation of Gustave le Gray’s experiments with light, layers, and time into a hypnotic musical syntax.

In the spirit of lush romanticism, I wanted to end with César Franck’s Prélude, Choral et Fugue. Just like Chopin’s music, this work of Franck’s is a love letter to piano playing. With its virtuoso sweep and expressive chromaticism, it is the result of the revolutionary writing that Chopin brought to the instrument.

Program listing and tickets for July 6th’s piano recital The Golden Age can be found here. Want to make a weekend out of it? July 5th will feature the ever dynamic Lao Tizer Band, with a diverse program that will definitely get you grooving.