Archduke Weekend – a tradition worth repeating

Beethoven’s “Archduke” Trio is hard. Really hard. It contains some of the most awkward figuration in passages that should sound glittering and effortless. And yet, it is one of the most magnificent works of chamber music. I guess it’s true that nothing so beautiful is gained without great difficulty, and I’m certainly thankful for the chance to play it year after year.

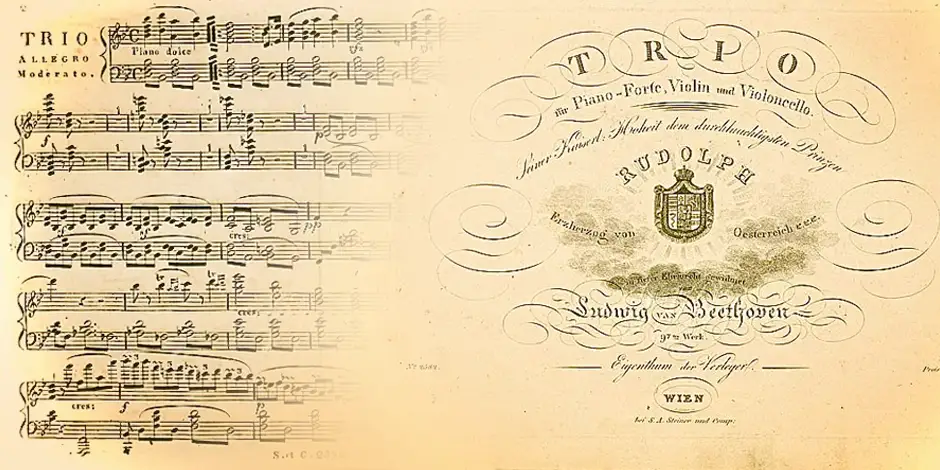

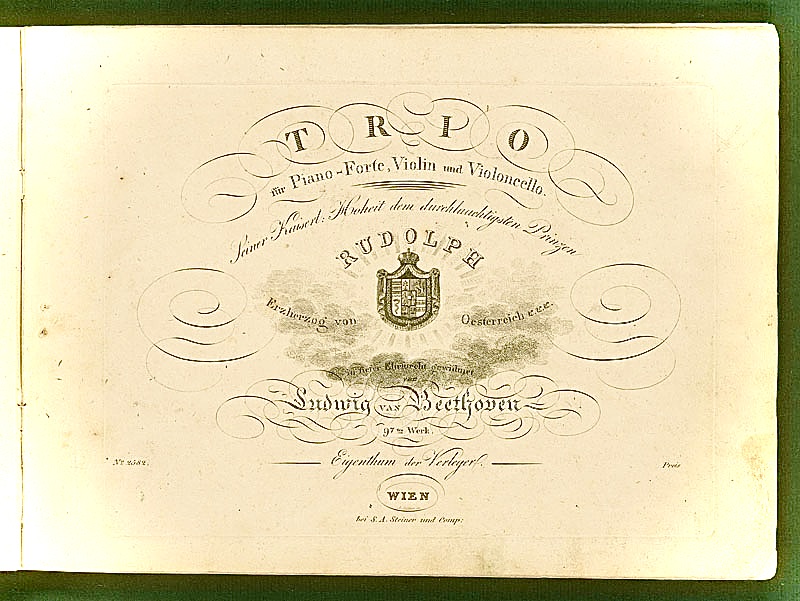

I’m sure that its inexhaustible beauty is a large reason for why Beethoven’s Op.97 “Archduke” piano trio became Garth Newel’s beloved tradition, back in 1983 when the ensemble in residence was Luca and Arlenne DiCecco and Paul Nitsch. The musical weekend was originally conceived as a collaboration with the Homestead, with the concert designed to be a special event promoted by American Express. Since performances were held at the hotel it became a black tie affair because of the requisite dress code. The hint of royalty given by the trio’s nickname (derived from being dedicated to Archduke Rudolf of Austria) made it an appropriate title for the glitzy ocassion.

Archduke Weekend this year launches our 50th Anniversary Season, with a three day musical exploration that takes us from Beethoven’s beginnings (May 26th), his compositional impact (May 27th), to the crowning Archduke Trio (May 28th), still resplendent after 40 years. And for the first time in person, we’ll be joined by Beethoven scholar Stephen Whiting from University of Michigan, whose delightful talks will prelude the music of each concert.

We will go from stormy to serene with the opening Friday concert, paralleling the sentiment of Founder’s Day by starting with Beethoven’s precursor to his string quartets. Beethoven’s Op. 9 No. 3 string trio is robust and passionate, opening with immediate intensity as a four note motif descends into the angst of a young man of 28. One can see Beethoven’s desire for more strings with the double stops of this opening, as if already envisioning the four parts of a string quartet that would eventually replace these trios in the concert halls.

As a pianist, Beethoven had naturally started composing on the keyboard, writing many works for himself to play as a soloist. It’s interesting to consider why he chose to make his compositional debut a set of piano trios, when it would seem much more likely that his Op.1 would be a set of piano sonatas. With this deliberate choice, Beethoven wanted to show the world that he was a serious chamber music composer first.

By the time Beethoven got to his 6th piano trio, he was well into his middle period and an older and wiser man. Instead of the youthful hubris and energy of his Op. 9 string trios, Beethoven’s Op.70 no.2 is profoundly introspective. Its easy lyricism and clarity favor Haydn and Mozart, and I often think of this trio as Schubertian in its breadth and beauty.

We move from the strapping youth of Beethoven to the teenage angst of Gustav Mahler, who wrote his only piano quartet nearly a century later when he was still a student. He was only around 15 or 16 years old, but one can already see his depth of expression within the impassioned and late romantic style of the work.

Most European composers of the late 19th century could cite Beethoven as an influence, but for Mahler it was an obsession. He modelled many of his symphonies on Beethoven’s, and gained fame as a conductor for his interpretations of Beethoven. They even shared the same natural landscape of the Austrian countryside that would have undoubtedly inspired both of them. Each had a habit of walking the countryside to get their creative juices flowing, and reflected the awe they had for nature in their music.

Much closer still was Brahms, born just 6 years after Beethoven died. He was publicly proclaimed to be “Beethoven’s heir” by Robert Schumann when he was only 20, an onus that he was not altogether pleased to bear. But begrudgingly or not, Brahms could not escape the mountain of what Beethoven had accomplished, from the architectural clarity of his compositions to the complexities of texture and rhythm that magnify their expression. Brahms’s A major piano quartet in its expansive introspection recalls Beethoven’s Op.70 no.2 piano trio as well as the serene beauty of his Op.97 Archduke piano trio. In particular, the meditative opening of the piano quartet brings to mind the stillness we feel in the prayerful slow movement of the Archduke.

The Archduke Weekend stands as Garth Newel’s most time honored tradition. Beauty that is earned – a perfect description of Garth Newel’s 50 years.

- Jeannette Fang