An introduction to GNMC’s first Sonatenabend: Beethoven Sonatas

In Old Italian, the word “sonata” derives from “sonare”, which means, “to sound”. Which doesn’t seem very helpful until it’s pointed out that in music, it’s used as an action.

“To sound” means “to play”. To play an instrument. Different from “cantata” (“to sing”).

So, sonata is a designation; a work for instrumentalists. And hooray for that, because, quite honestly, you don’t want to hear me sing. I really can’t have everyone bewildered and looking for the angry mosquito.

Throughout time, the sonata grew to become an organizational principle, with a logic of narrative building that frilled and morphed with each stylistic period. And with his 32 piano sonatas, 10 violin sonatas, and 5 cello sonatas, this genre of musical composition really culminated with Beethoven.

47 published sonatas (as well as several posthumously published ones) is pretty comprehensive. You could program multiple years worth of music with all his sonatas and you wouldn’t get bored. Because Beethoven, being such a lovely human hurricane of creativity, mastered and then reinvented the form. By pairing his 4th piano sonata (Op. 7) with his last cello sonata (Op.102 no.2) on the opening concert of our Fall Foliage Festival, we wanted to illustrate how the change in Beethoven’s compositional intent altered the sonata from his early years to his late.

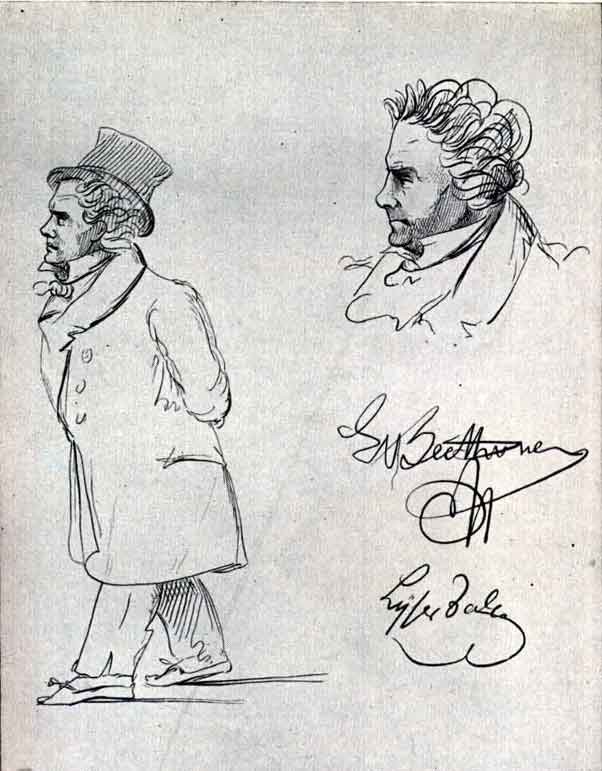

Written in 1796, within the early years of his arrival to the musical mecca of Vienna, Beethoven’s 4th piano sonata was written to dazzle.* He came to Vienna to establish himself as a virtuoso pianist and composer, and his early piano sonatas were his announcement basically saying “Behold the seriously impressive pianist who writes music for only the most advanced pianists.”

His need to establish himself was also due to the fact that he was the first major composer in Vienna to essentially be a freelancer, making his living from the demand for his music rather than by an appointment.

With his 4th piano sonata, Beethoven clearly wanted to show off. Not only did he want to wow with the technical prowess of the writing, but he wanted the enhanced difficulty to illustrate the larger capabilities of the new Viennese fortepianos of the time. Beethoven is known to have tried the new pianos from Stein, which did away with the checking mechanism that catches the hammer after it strikes the strings, as well as the ones of Anton Walter, whose innovative action prevented the hammers from bouncing back, and whose larger soundboard and bridge created a greater and deeper sound. It makes sense then that Beethoven’s 4th piano sonata was his testing ground for what the new instruments could handle. The sonatas’s fast repeated notes, fortissimo chords, tremolo-like figuration, and sudden dynamic changes seems to bolster the point that Beethoven preferred the greater control and dynamic range of the Walter fortepiano.

And the sonata utilizes the entire range of the piano, with rapidfire and ebullient passagework that traverses 5 to 6 octaves in a matter of seconds. Not only do phrases react to each other with wide leaps, but even within a single melody there are large intervallic jumps. And by pairing opposing elements, Beethoven creates a glittering energy to the first movement. For instance, it opens with pulsating repeated notes that serve as an agitated undercurrent to a strangely sparse chordal theme. This forward propulsion is the primary force of the entire movement.

Then there’s the fact that Beethoven used the 4 movement structure for this sonata, which was a format associated with symphonies and string quartets. By inserting a minuet movement between the 2nd and the 4th movements, perhaps Beethoven meant the “sonata” to be taken as a serious large scale work. This also gave Beethoven more room to stuff in a plethora of attractive (and sellable) melodies and ideas.

Skip ahead to 1815, when Beethoven wrote his last two cellos sonatas. These sonatas were so unprecedented in their construction that the contemporary Viennese society was befuddled. If you consider how Schubert was still writing 4 movement sonatas years after Beethoven had grown tired of the scheme, you get an inkling of how much of an outlier Beethoven became. No longer needing to prove his worth, Beethoven instead seemed to be guided by an obsession within himself.

First, he cuts the fat. Who needs the easy listening of the minuet movement of the classical 4 mvt sonata structure? Who needs all these notes and long expositions? Who needs an introduction? Not this sonata.

Then, instead of doing the expected thing and making the outer movements of the sonata the longest, Beethoven spends the most time on the middle slow movement. And you’ll be very glad for this, because it’s a movement that’s profoundly beautiful. Beethoven’s slow movements are some of the most honest expressions in all of music (IMHO), and the slow movements of both Op.102 no.2 and Op.7 make me feel grateful for the experience of playing them.

And then, bizarrely, he makes the whole last movement a fugue. A fugue whose subject seems simple, yet is off-kilter and whimsical, allowing for playful interchanges between cello and piano that become more and more complex and ecstatic as the two integrate.

This fugue is the first occurrence of Beethoven’s obsession with contrapuntal writing, which is prominent in his late piano sonatas and string quartets. They are insanely difficult, daring, and progressive, and they challenge our limits in every way. In this way, I feel like Beethoven challenged everything that was taken for granted in music, and most notably, the sonata itself. If Beethoven’s intent in his mid-20s was to prove his own worth, his intent at the end of his life was to transcend the form.

Our Beethoven Sonata Evening (Sonatenabend I) will be October 18th, at 5pm. Tickets are still available at: Sonatenabend I